Approved by Congress and signed by President Trump on January 29, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement is one big step closer to entering into force. Mexico was first to ratify the trade pact on June 19, 2019. Canada’s House of Commons will be taking up the USMCA this February.

For the time being, the North American free trade agreement – NAFTA – remains in force. Even with Canada’s ratification, expected in April, time will be needed for the three trade partners to meet their obligations under the new pact. Mexico, for instance, has committed to legislative action on labor reforms. Once each partner has served notice of compliance, the Agreement between the United States of America, the United Mexican States, and Canada (USMCA) will be set to enter into force “on the first day of the third month following the last notification,” or roughly 60 days later.

Still, after several rounds of negotiations that began in August 2017, a finalized USMCA is now in the home stretch toward implementation. You can find the text of USMCA here; the text of NAFTA is here. Following is a summary of what’s new in USMCA.

USCMA: 21st Century Reboot

The 21st-century reboot of the 25-year-old trade pact preserves or builds on much of the original while addressing issues that weren’t on the table back in the 1990s.

For instance, USMCA Chapter 19 on digital trade (the first of its kind) sets “predictable rules of the road” for e-commerce, including a prohibition against duties on digital content and commitments to protections for online consumers, the privacy of personal information, and for internet companies against liability for the content their users produce. The pact recognizes the legal validity of electronic signatures, clearing the way for cross-border electronic trade.

USMCA chapters on intellectual property (Chapter 20), labor (Chapter 23), and the environment (Chapter 24) impose new, enforceable obligations on the trade partners in line with a quarter of a century of technical and public policy developments on those fronts.

For instance, the partners promise not to circumvent their environmental laws to boost trade or attract investment. They are required to meet their obligations under seven multilateral environment agreements (MEAs), including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. There are new articles aimed at protecting coastal and marine environments, improving air quality, and supporting sustainable forest management. (It should be noted that, while acknowledging these articles as improvements, environmental advocates criticize USMCA for not paying heed to climate change.)

Perhaps more significantly, the partners’ environmental and labor obligations, which are covered in parallel accords under NAFTA, are now incorporated in the core text of the agreement. Moreover, these new obligations are fully enforceable under USMCA, which includes mechanisms for resolving disputes. For example, Mexico has not only agreed to legislative actions that recognize workers’ rights to collective bargaining and democratic unions, it has also agreed to a “rapid response mechanism” to monitor and expedite enforcement of these labor reforms.

USMCA: Curbing Non-Market Practices

Also new in USMCA are articles aimed at curbing non-market practices that distort global commerce.

This troublesome 21st issue had yet to emerge when NAFTA entered into force in 1994. But then, China had not yet emerged as a leader in global trade. Concerns about China’s non-market practices were addressed when its 2001 admission to the World Trade Organization was made contingent upon its agreeing to a phased program of market liberalization. While these reforms were under way, there was to be a grace period of 15 years during which China’s WTO trade partners would be permitted to treat it as a non-market economy (NME) for purposes of anti-dumping enforcement. Come 2016, China expected and claimed market economy status. The U.S., EU, and Japan have challenged that claim. (Last July, China asked the WTO to suspend the dispute it had filed in this matter.)

While not mentioned by name in the text of the agreement, China is called out in the U.S. Trade Representative’s USMCA fact sheet on a new requirement in Article 32.10: “If any USMCA party undertakes to negotiate a free trade agreement with China or other non-market economy, that party must notify the others of its intention.” The remaining two parties can review any such pending agreement between the third party and an NME: If its terms are not acceptable, they can withdraw from the trilateral USMCA and enter a bilateral agreement.

Other articles may be looked to as models for terms the U.S. will seek in future trade agreements with other countries, including China. Chapter 22 expands the definition of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to include not only government-owned companies but also companies under government control, even if government ownership is limited to a minority share. There are some carve-outs for Mexican State Productive Enterprises. However, direct government subsidies to SOEs are generally prohibited. Chapter 27 requires that the partners criminalize acts of corruption by domestic and foreign government officials. Chapter 33 includes commitments to refrain from currency manipulations.

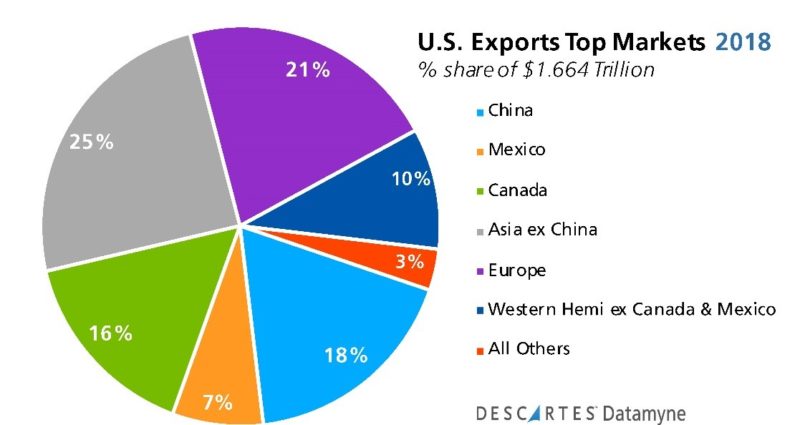

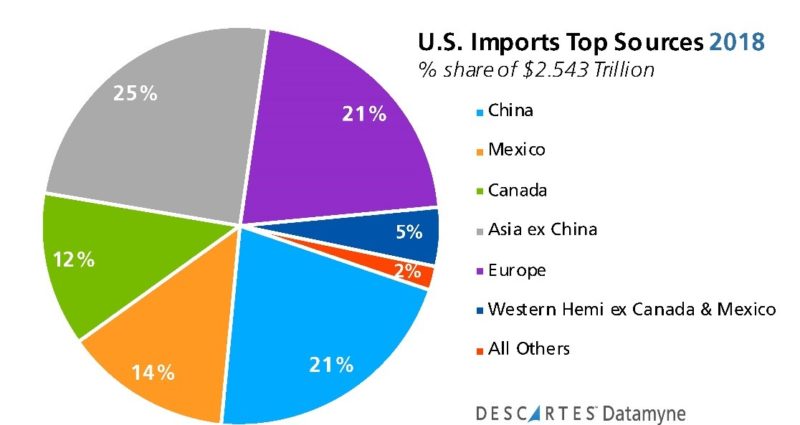

USMCA not only resets the terms of U.S. trade with its North American neighbors, it sets the goalposts for redefining the relationship with top trading partner China. Together, these three nations alone accounted for 41% of U.S. exports, 47% of imports in 2018, as illustrated in these charts:

USMCA: A Boost for U.S. Agricultural Exports

Canada is the top and Mexico ranks third among destinations for U.S. agricultural exports. The U.S. is the top market for both Canada’s and Mexico’s agricultural products. All food and agricultural products that have zero tariffs under NAFTA will remain at zero tariffs.

USMCA Chapter 3 acknowledges that all three trading partners provide government support to their agricultural sectors. The new agreement commits each to “consider domestic support measures that have no, or at most minimal, trade-distorting effects or effects on production.” That’s a straightforward statement of principle. Putting the principle into practice can be complicated.

Consider Canada’s system of managing its domestic supply of dairy products. Canada matches domestic production to consumption and sets quotas limiting tariff-free dairy imports. The program was left in place under NAFTA. In 2017, Canada created new product classifications in its supply program that permitted domestic products to be sold at prices undercutting U.S. products in Canada and other export markets. The U.S. made rolling back what it saw as a barrier to trade top of agenda in renegotiating NAFTA. Under USMCA, Canada agrees to eliminate milk classes 6 and 7 and their associated prices. Canada will also apply export penalties on shipments of skim milk powder, milk protein concentrates, and infant formula over specified quantity thresholds.

In addition, Canada is setting new tariff rate quotas for selected U.S. dairy products, including milk, cheese, cream, butter, yogurt, and ice cream. TRQs will be phased out for whey in 10 years, for margarine in five years.

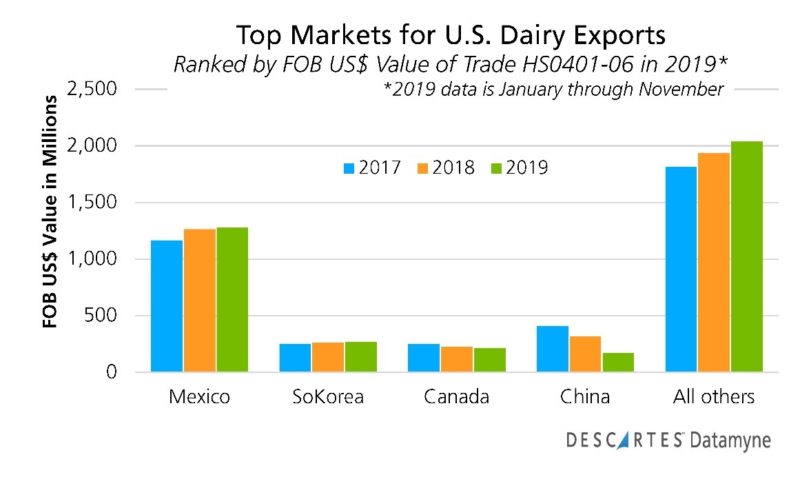

Here’s the benchmark data for U.S. dairy exports against which to measure the effects of this USMCA provision:

Other changes of note affecting agricultural products include an agreement between the U.S. and Canada to treat each other’s wheat as if it were their own. A side letter between the U.S. and Mexico lists cheeses that can be sold in Mexico without restrictions based solely on the names of the cheeses.

In a first for a U.S. trade agreement, USMCA provides a framework for cooperation on reviewing and approving biotechnology innovations in agriculture including DNA technology, gene editing, and beyond.

USMCA: Rules of Origin

USMCA Chapter 4 covering the rules of origin that determine what qualifies as “made in North America” delivers some big changes for passenger vehicles, trucks, and automotive parts:

- The regional content requirement for cars and light trucks will be raised from NAFTA’s 62.5% to 75% by 2023. The requirement for heavy trucks is raised from 60% to 70% by 2027.

- There is a new requirement that 70% of steel and aluminum used to make cars and trucks be sourced from North America.

- For the first time, minimum-wage requirements are set: By 2023, at least 40% of production labor must be paid at $16 per hour.

- Side-letters from the U.S. promise exemptions from potential future U.S. Section 232 tariffs on selected automotive products made in Mexico and Canada.

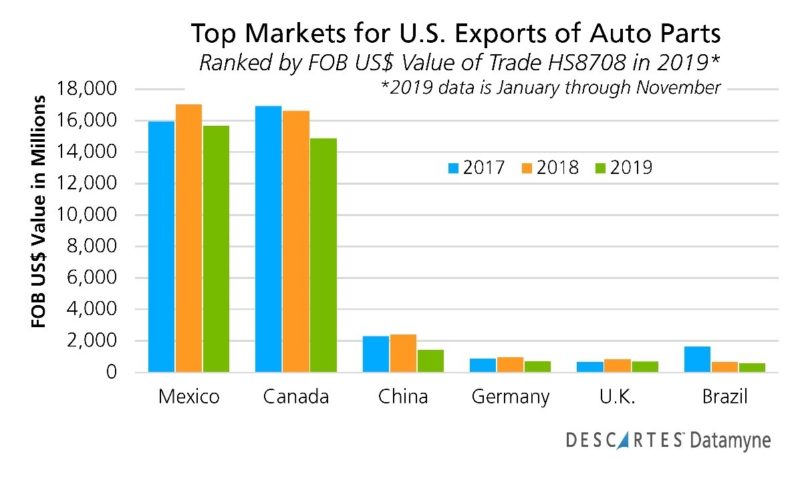

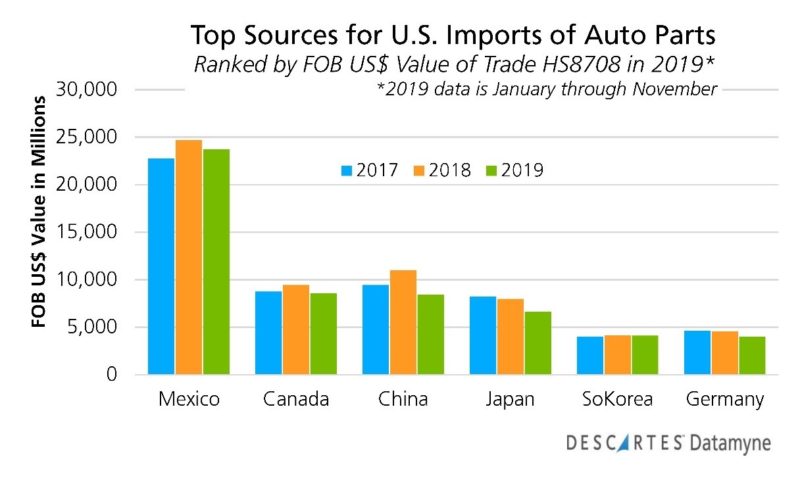

U.S. cross-border trade in these products is already concentrated in North America, as this benchmark data on auto parts indicates:

The side-letters offer assurance that carmakers’ continental supply chains won’t be disrupted by Section 232 tariffs. (In May 2018, the U.S. initiated an investigation into whether auto and auto parts imports merited tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. A final decision on imposing these tariffs has been pending for some time.) On the other hand, the new requirements will almost certainly raise production costs.

Rules of origin related to textiles and apparel goods are also changing. A separate Chapter 6 covers new requirements:

- Sewing thread, narrow elastic fabrics, pocketing, and coated fabrics are added to the list of inputs to be sourced regionally.

- Some tariff preference levels (TPLs) that allow exemptions to rules of origin requirements for selected inputs are reduced for U.S. imports from Canada and Mexico. TPLs for U.S. exports to Canada of finished goods are raised.

- The list of textile inputs manufacturers can use because they are not available in North America is expanded. The de minimis percentage of non-originating inputs is raised from 7% to 10%.

Importantly, USMCA provides for ongoing review and revision of rules of origin. Any of the three partners may initiate a meeting to raise issues as they arise. USMCA also directs a new tri-lateral committee on textiles, charged with reviewing USMCA’s impact on apparel sales, to be established.

USMCA: The Sunset Clause

The committee on textiles and apparel trade will not be the only forum for ongoing review, discussion and tweaking of USMCA rules and processes going forward.

USMCA also establishes a committee to discuss and develop activities that enhance and promote North American competitiveness (Chapter 26).

There are to be committees addressing issues that arise concerning agricultural trade (Chapter 3), rules of origin and origin procedures (Chapter 5), trade facilitation (Chapter 7), transportation services (Chapter 15), telecommunications (Chapter 18), infringement and enforcement of IP rights (Chapter 20), SOEs (Chapter 22), and macroeconomics (Chapter 33), as well as specialized subcommittees and working groups.

Topping them all is Chapter 34’s “joint review” of USMCA in its sixth year. This mechanism for renewing or ending the trade pact has been referred to as USMCA’s Sunset Clause.

Here’s how it will work: The term of the agreement is 16 years. However, in year 6 the three partners are to review the trade pact. They may, at that time, confirm that they wish to extend the trade pact for a second term of 16 years. If USCMA is reconfirmed and extended, the pact will come up for review and confirmation again in another 6 years. Failing a three-way buy-in, USMCA will be allowed to expire at the end of its existing term – that is, after 10 years, during which the three parties are required to meet at least annually to try to resolve their differences in a renegotiated agreement.

All these provisions for reviewing and modifying USMCA suggest that this trade pact will be more fluid and adaptable than NAFTA. The ability to respond more quickly to trade issues as they emerge is certainly a positive gain for the regional market’s global competitiveness. But it can also mean more uncertainty about shifting rules of the marketplace for businesses trying to plan beyond the near-term.

Related:

From the blog:

- U.S.-China Phase One Agreement Focuses on Relationship Reset

- NAFTA Negotiations: Can Round 8 Roll over Sticking Points?

- USTR Outlines Objectives in Renegotiating NAFTA

Resources:

USMCA’s extensive new rules of commerce, and the provisions for their ongoing review and modification, pose a challenge for businesses not merely to keep abreast of and in compliance with the changes, but to turn them to competitive advantage. The Descartes Global Trade Content product suite helps meet the challenge with software-as-service solutions to integrate customs information and trade regulations with enterprise information and operation systems, and trade-data driven market intelligence. Ask us for a consultation.